Astronomers uncover the topsy-turvy atmosphere of a distant planet

The gas giant WASP-121b, also known as Tylos, has an atmospheric structure unlike any we have ever seen, and the fastest winds on any planet

By Alex Wilkins

18 February 2025

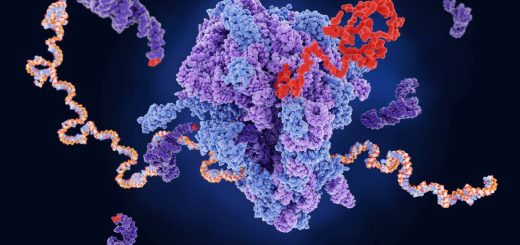

The three layers of the atmosphere of the gas giant Tylos

ESO/M. Kornmesser

The atmosphere of a distant world has been mapped in detail for the first time, revealing a strange, topsy-turvy weather system, with the fastest winds ever seen inexplicably blowing around the planet’s stratosphere.

Astronomers have studied WASP-121b, also known as Tylos, since 2015. The planet, which is 900 light years away, is a vast ball of gas double the size of Jupiter, and it orbits its star extremely closely, completing a full orbit in just 30 Earth hours. This close orbit heats the planet’s atmosphere to temperatures of 2500°C, hot enough to boil iron.

Read more

We live in a cosmic void so empty that it breaks the laws of cosmology

Advertisement

Now, Julia Seidel at the European Southern Observatory in Chile and her colleagues have looked inside Tylos’s scorchingly hot atmosphere using the observatory’s Very Large Telescope, and they found it has at least three distinct layers of gas moving in different directions around the planet – a structure unlike anything astronomers have ever seen. “It’s absolutely crazy, science fiction-y patterns and behaviours,” says Seidel.

The planetary atmospheres in our solar system share a broadly similar structure to one another, where a jet stream of powerful winds blowing in the lower portion of the atmosphere is driven by internal temperature differences, while winds in the upper layers are more affected by temperature differences created by the sun’s heat, which warms the daylight side of the planet but not the other.

Yet in Tylos’s atmosphere, it is the winds in the lower layer that are driven by heat from the planet’s star, travelling away from the warm side, while the jet stream appears to be mostly in the middle layer of the atmosphere, travelling around Tylos’s equator in the direction of the planet’s rotation. An upper layer of hydrogen also shows jetstream-like features, flowing around the planet but also drifting outwards into space. This is difficult to explain using our current models, says Seidel. “What we see now is actually exactly the inverse of what comes out of theory.”